Singin’ With the Band

Ethan Johns Brings Tom Jones Back to His Roots

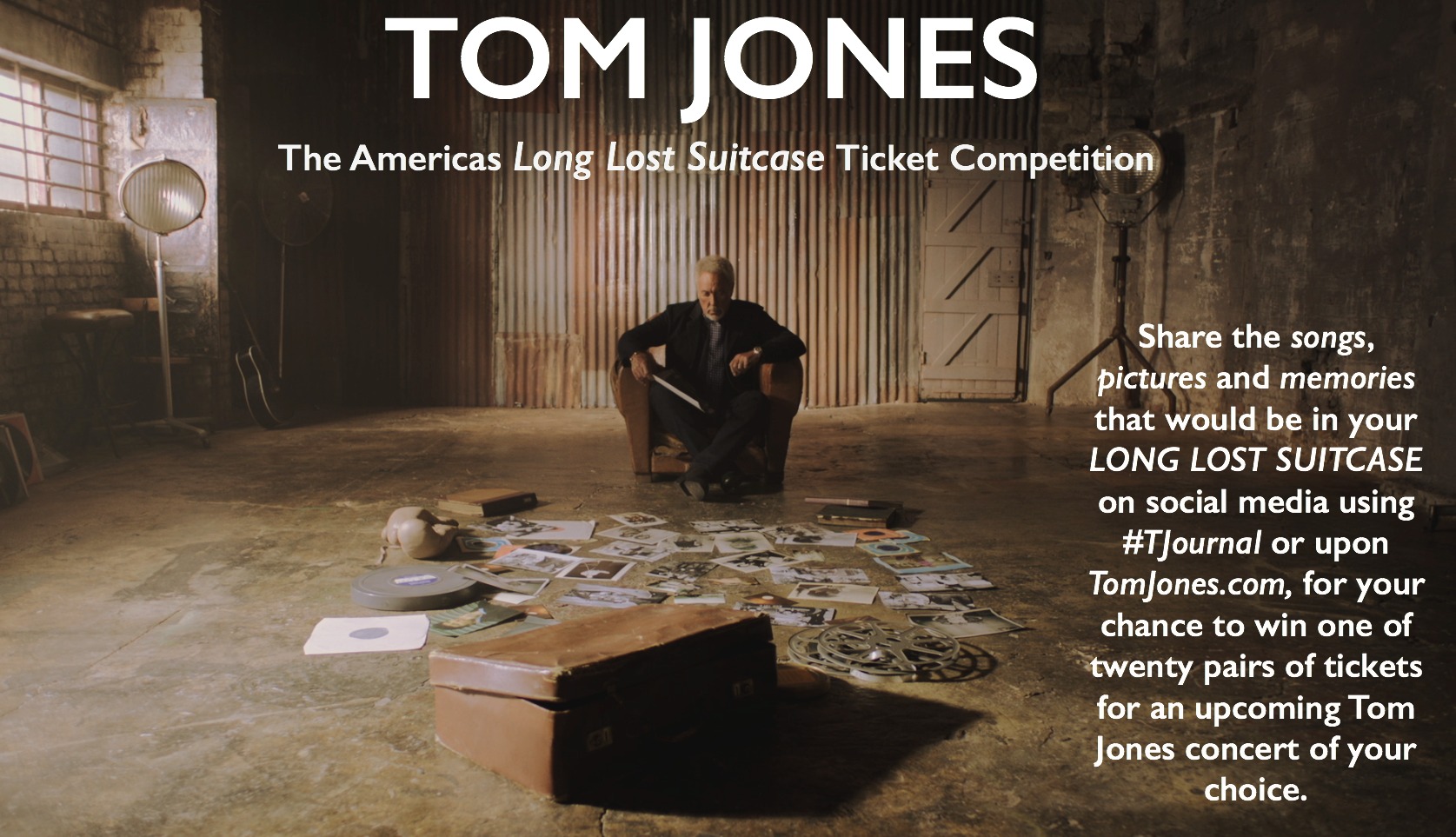

Remember what it was like when you were a kid, how much fun you’d have when you started making music with your mates?” asks producer Ethan Johns. “Just the four of you, sitting around, playing live and making music. That’s what this is.” “This” is Long Lost Suitcase, the third in a series of albums Johns has produced for legendary singer Tom Jones, following the acclaimed Praise & Blame (2010) and Spirit in the Room (2012). The disc, released by S-Curve Records in October 2015, follows the same winning formula as its predecessors: putting the singer in a studio with top musicians and letting him do what he did in the beginning of his career—sing live with a great band. “Ethan knew that I started with a small band in Wales when I used to play the pubs and clubs—a rhythm section, and that was it,” Jones explains.

“I knew some of the things he had done, with Ray Lamontagne, The Kings of Leon and Ryan Adams. I asked him what he had in mind, and he said, ‘I’d like to get you into a studio with very few musicians and just get to the essence of your voice,’ which he felt hadn’t been done before.” “To get the opportunity to put a microphone in front of a singer like Tom, who’s lived the kind of life he has lived and the experiences he can put into delivering a lyric, with that voice, that was just too good an opportunity to miss,” Johns says. All three albums were recorded by engineer Dominic Monks, whom Johns had met at Peter Gabriel’s Real World Studios in 2007 while mixing Crowded House’s Time On Earth. “I was working in a very small control room, struggling to get a decent sound, so I gave Dom a crack at it,” Johns recalls. “I had spent three or four days at it, and he got a staggering sound in about 15 minutes. He walked in, 24 years old, and didn’t even bat an eyelid. So I was, like, ‘Right, do you fancy coming and working with me?’

By that point, I’d engineered almost every record I’d ever made, and I really wanted to take on an apprentice, to work with someone young to whom I could pass on what I’d learned from my dad.” Their first project together was Ray LaMontagne’s Grammy-nominated Gossip in the Grain in 2008, and they have been working together ever since. While the first two albums were recorded at Real World, Suitcase was tracked, mostly, at The Distillery in Somerset, a studio built by musician Sam Dyson initially to record his own band, The Chemists. Designed by Neil Grant (who also designed Real World), The Distillery boasts a fine mic collection, tape machine and a live room with a stone floor mezzanine. While the studio houses a Neve 8036, Suitcase was recorded through a Universal Audio 610 console built originally for Frank Sinatra’s home studio by Bill Putnam. “We ran Tom’s vocals through that,” says Monks. “It’s the most extraordinary sounding bit of gear I think I’ve ever faded up.”

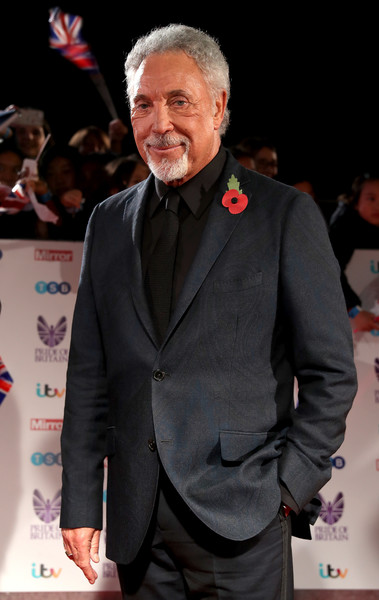

Engineer Dominic Monks setting up one of only a few drum mics with drummer Jeremy Stacey.

Suitcase was tracked to an Otari MTR-90 analog deck, using ATR Magnetics tape at 15 ips. “Sixteen tracks is fine for us,” Monks explains. “When you only have three or four mics on a drum kit, and a small band, that’s plenty of space. And a wider track means less noise and a richer sound all around.”

Song suggestions came mostly from Johns, Jones himself and Jones’s son, Mark Woodward, who works closely with his father. The main criteria was that they resonated with Jones. “Ethan knew I love gospel, country and blues,” says Jones, “so that’s what we did.” The resultant list included, among others, Willie Nelson’s “Opportunity to Cry,” Little Willie John’s “Take My Love (I Want to Give It),” Los Lobos’ “Everybody Loves a Train,” the spiritual “He Was a Friend of Mine,” Henry Russell’s “Tomorrow Night,” The Rolling Stones’ “Factory Girl” and Hank Wiliams’ “Why Don’t You Love Me Like You Used To Do.”

“When I learn a song, I can actually see the story,” Jones explains. “On ‘Everybody Loves a Train,’ for example, I see the concrete platforms and the people. Where are these people going? I put myself in the story of the song. I’m living it as I’m singing it. And I’m seeing it. Every song is like a mini movie to me. If I’m not seeing it, I can’t expect other people to.”

“Tom can sell you anything,” Monks smiles. “He actually used to be a vacuum cleaner salesman, door to door. And I’m sure he sold a lot of them.”

Bring in the Band

Johns assembled a core group of topflight musicians to back Jones for three separate five-day sessions in 2013: the last week in March, last week in June and first week in November, recording 11, nine and nine songs, respectively.

Besides the talented Johns on guitar and other instruments, the producer brought in guitarist Andy Fairweather-Low, an old friend, it turns out, to both he and Jones. “We both come from South Wales,” the singer notes. “I used to see him playing in London at the same time I was, with his band, The Amen Corner. And Andy was friends with Ethan’s father, Glyn—he remembers Ethan when he was a baby.”

Says Johns: “I’ve known [Andy] all my life. He was a hero of mine, growing up. He would come ‘round to the house and would always take time to help me restring my guitar or show me a new chord. So to be able to stand in a room with him and make this record was a real treat.”

Bass was handled by either Dave Bronze or Ian Jennings, while the drummer was another veteran, Jeremy Stacey. “A lot of thought goes into what Jeremy plays,” Johns explains. “He’d bring maybe three kits, at least five snares, 15 or 20 cymbals. He’d even vary what sticks he was using or the type of hardware.”

The band played live with Jones singing live in the studio, all grouped together closely, without headphones, Jones included. “To me,” he says, “it was a more natural way of recording. When I was first singing in pubs in Wales, we’d rehearse in the pub, we’d get some songs together, and then we’d go out and try them. There were no preset arrangements. They were done on the spot.”

The method is one Johns generally prefers on nearly all his recordings. “Everything sounds better if you do it that way,” he explains. “You’re pitching, you’re tuning, you’re timing—you’re balancing yourselves. That’s a fairly fundamental skill as a musician. If you’re stuck in headphone world, you’re isolated from everybody. Everybody’s got their own headphone mixes, listening to their own mix. You can’t get a musical conversation going. Overdubbing is a one-way conversation. If the thing you’re playing off is stagnant, and not responding to what you’re playing, then what are you doing? Who are you playing for? You’re certainly not making music with the band. You’re doing something else. To me, it’s criminal to take a singer like Tom, go away and record a track without him, and then ask him to come in and sing it on his own.”

Johns and Monks set up the room with the musicians close to each other, separated by low gobos, and Jones facing them so that all could see and hear each other. “You really want everybody to be primarily listening to the vocalist,” Johns explains, “because that’s where the beginning of a great take will occur, in the vocal performance. That should be inspiring and leading and informing every choice that you make as a musician. We’re all trying to catch the same wave. Tom responds as much to what we’re playing as us responding to him. You don’t have one thing without the other. If we’re not feeling it, all five us, it’s not gonna happen.”

The Universal Audio console built by Bill Putnam for Frank Sinatra.

The method suited Jones just fine. “They’re listening, they’re hearing the expression in my voice—they’re living in it the same as I am,” he says. “Jeremy does little things with his brushes, for example, following my phrasing. It’s like he reads my mind—he seems to know what phrasing I’m using and puts in accents to accent it. He changes things as I’m changing them. It’s extraordinary.”

Monks would mike Jones with a classic RCA 44, which, he notes, had benefits besides its inherent tonal qualities. “Half the drum sounds come in the back end of the 44,” he explains. “Everybody is coming down Tom’s mic. You can solo Tom’s mic and just enjoy the records. That’s the sound, basically. I would treat that as if it was the main microphone, as you would a main pair in a classical recording. Everything else in the room is a spot mic.”

For louder tracks, the engineer would place a Shure SM7 directly next to the 44. “The 44 is a figure-8 mic, so if you stick a cardioid—like the SM7, which has great rejection out the back—next to it and mix them together, you end up with a hypercardioid microphone.”

Johns played his guitars through a 10W or 15W Magnatone Lyric amp, a Vox AC4TV and a Fender Excelsior, while Fairweather-Low had a 15W Supro, with a single 12-inch speaker. “The key to recording in this manner is you’ve got to be getting a great sound, but at low volume,” Johns explains. “So lots of very low-wattage amps knocking around.” The Vox was used for the grungier leads, though Johns sometimes would use a diminutive 1W Marshall. “It’s a little boutique handmade Marshall, with incredible sound.”

Monks miked the amps with a Coles or Telefunken C12, often with a Unidyne SM57 alongside; for smaller combos, a 57 or a Sennheiser 421 in the back, mixed together with the front mics, out of phase, onto a single track. “That’s a trick I sometimes do on those really small amps, when you’re trying to get some of the low-end resonance output from them,” Monks says. “If you just put a mic in front, they can sometimes be a bit small.”

For Stacey, Monks had the drummer bring his own vintage AKG D30 bass drum mic, supplementing a selection that included C12s, U 87s, Coles, the 57s and AKG D19s, the latter for louder tracks. “It would change drastically from track to track,” Johns says. “I’d marvel at how Dom would change his miking technique depending on the sound Jeremy was making.”

Four additional tracks were cut elsewhere, all of which had been attempted previously, but, upon late review of existing tracks, not to Johns’ satisfaction. So a year after the last Distillery recordings, Jones, Johns and Monks went to Real World and tracked “Elvis Presley Blues” and “He Was a Friend of Mine,” with just Johns on a tremoloed guitar and Jones singing alongside him. In a rare instance of overdubbing, Johns doubled his guitar, producing a unique stereo effect. “We only did two takes of the song,” the producer reveals. “We put the guitar track from the alternate and flew it into the first pass—that’s that guitar sound.” Two more, “Factory Girl” and “Honey, Honey,” were recorded anew at Paul Epworth’s studio, The Church, with Irish band Rackhouse Pilfer.

Johns mixed most of the album himself at his home studio, Three Crows East. Since he doesn’t own a 16-track analog machine, the tracks were transferred to Pro Tools at The Distillery, then converted to analog via a set of RADAR converters before being mixed through his API analog console and recorded to a Studer C37 ¼-inch 2-track.

“I do quick mixes, almost like roughs,” Johns reveals. “There’s very little processing, no program compression or bus compression, and very little EQing on anything. It’s all balance. And I spend no more than 30 or 45 minutes on any song, and then just live with them for a few weeks.”

Occasional slap echo does appear, Johns using either an Electro-Harmonix Memory Man or Lexicon PCM42, in lieu of several vintage Echoplexes he has around. “It’s pretty crunchy; it has its moments,” he laughs. “There’s a lot of old gear here, so it’s always a bit of ‘fingers crossed.’ You’re running tape, an old console, tubes everywhere. You just hope that nothing’s gonna fail catastrophically during the live take, during the keeper.”

Tracks like “Why Don’t You Love Me Like You Used To Do” can even end up with a mono mix, as was the case here, giving it an authentic 78 rpm sound. “I think one of the enemies of creative record making is decision deferral,” Johns says. “You should just trust your instincts. I mixed that song four or five times, and just one day went, ‘You know what? I’m gonna mix this mono.’”

The process, from beginning to end, was just Tom Jones and his band, playing songs. “You can hear the joy in those songs, in his voice, because Tom is having a good time,” Johns states. “The musicians are being allowed to play and express themselves and perform. And Tom is just sitting in front of people that he loves, making music he wants to sing. When you hear the smile in his voice, it’s real.”

Article written by: Matt Hurwitz for Mix Magazine

Photos: Mark Woodward

Article available online here