Julian Marszalek , May 13th, 2010 10:21 http://thequietus.com/articles/04253-tom-jones-interview-praise-and-blame-elvis-presley-johnny-cash-frank-sinatra-janis-joplin

Living legend and Wales' finest son talks exclusively to Julian Marszalek about his life, work and loves... and why a round of applause and a pint of decent ale are the only drugs he'll ever need.

Julian Marszalek , May 13th, 2010 10:21 http://thequietus.com/articles/04253-tom-jones-interview-praise-and-blame-elvis-presley-johnny-cash-frank-sinatra-janis-joplin

Living legend and Wales' finest son talks exclusively to Julian Marszalek about his life, work and loves... and why a round of applause and a pint of decent ale are the only drugs he'll ever need.

Watching those vintage clips of Tom Jones on long-forgotten The Beat Room TV show, dropping the full-throated bomb of his 1964 debut single, 'Chills and Fever', and ably backed by a full on rock'n'roll band, it's not difficult to wonder how things might have been. Quiffed and bursting with a barely contained youthful energy, it's one of the few occasions that Tom Jones the rock'n'roll singer is seen at serious odds with the image and reputation that followed to this very day.

In the 46 years since his singular baritone burst out of the valleys of south Wales, Tom Jones has lent his voice to pretty much every style of music that's buried itself into the public consciousness – pop, rock, showtunes, county, disco, electronica – you name it, he's done it. For his legions of fans, this gleeful style-hopping is a symbol of his versatility, a singer just as much as home with ballads as he is with music needing a more widescreen delivery. To his naysayers, Jones is little more than a tuxedoed entertainer happy to exploit trends with little regard for the impetus behind them.

Perhaps it's the image of the tight-panted cock-thruster dodging the ever-showering rain of underwear on stage that does him a disservice, but it can be easy to forget that Jones is a man with a passion for roots music that runs several fathoms deep. His appearance alongside a number of British blues luminaries in Mike Figgis' contribution to Martin Scorsese's series of The Blues films revealed a man exposing his emotions without the usual trappings of showbiz schmaltz and glitzy presentation. More often than not, he was no longer the Vegas crooner of legend but a man tapping into his very heart and soul to deliver a performance of uncharacteristic tenderness and undeniable human frailty. It was a side of the singer rarely seen even by his staunchest defenders or sternest critics, and one that had still to make its mark outside of that coterie of legendary musicians.

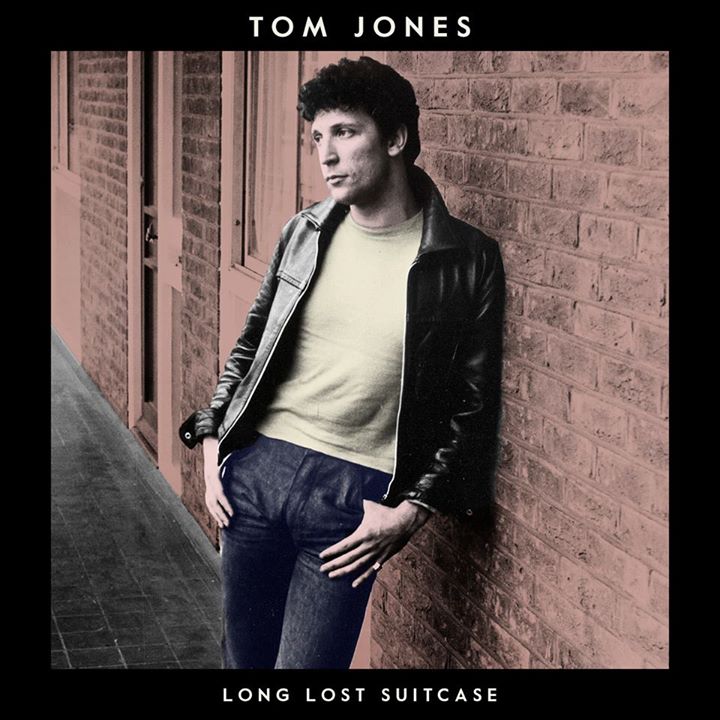

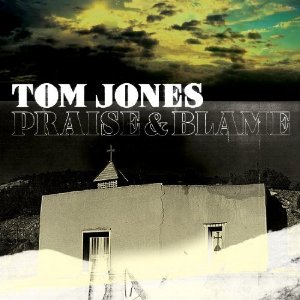

It's always been obvious that behind the façade of glamour, greasepaint and lights is a man who clearly loves music at its earthiest and most uncompromising form. What's also obvious is that this side of Jones is only fleetingly glimpsed and it's a fact that hasn't been lost on the man himself. Fast approaching his 70th birthday, Jones has hooked up with producer Ethan Johns, the man responsible for helming albums by Kings of Leon, Ryan Adams, Rufus Wainwright and Laura Marling, to deliver Praise and Blame, perhaps the most honest album of his long career.

Returning to his roots of gospel and the blues, Jones has eschewed the sheen of his most famous recordings in favour of dirt and red-raw honesty. Backed by a simple rhythm section and recorded live with no overdubs, this is the sound of Jones the Voice sailing into uncharted waters as he convincingly seeks redemption and a sense of peace. More importantly, this isn't another ersatz reading of Johnny Cash's American Recordings series as is currently favoured by artists and producers of a certain vintage, but something approaching a re-affirmation of why Jones does this in the first place.

Speaking to Jones via telephone in LA, The Quietus is struck by the warmth, enthusiasm and humour in that familiar baritone and it becomes clear that he isn't some huckster flogging his wares; Jones is genuinely stoked and excited by what he's achieved, and hopes that his long serving audience goes with him on the latest detour of this particularly long and winding road.

Your last album, 24 Hours, found you returning to the sound that made you famous in the 60s. Praise and Blame finds you going back further still to the music that inspired you to sing. Have you come full circle?

Tom Jones: I think so. I try different things because I like to do all different kinds of songs, you know? Sometimes it's difficult to know which way to go really. First of all I had to talk to a producer so I talked to Ethan Johns and told him that I wanted to do some spiritual stuff that means something but not overblown and he said, 'Well, that's exactly the way I work. I work with a rhythm section in the studio and we'll kick that around in the studio.; And that's a great way to work, I think, with everybody pitching and chipping in. When you've got the song and you've got the key, we kick the song around a bit until we get something that sounds natural.

What's drawing you to the spiritual side of things?

Well, I've been into spiritual music since I was kid. We always sang a lot of gospel stuff in the chapel and at funerals, funnily enough! I mean, the most famous one in Wales is 'The Old Rugged Cross'. Even at parties we'd have the old singsong on the weekend but you realise with that stuff that even though sometimes it's sad, it's also uplifting. When I used to sing in the pubs and the clubs in Wales we'd always put in a gospel-type song like 'Down By The Riverside', you know? And I realised that when rock'n'roll kicked in in the 50s that that's where it came from: gospel, country and blues.

Were you ever torn between spirituality and rock'n'roll in the way that Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis were?

Well, that's why I've called the new album Praise and Blame, because you can be praised for something and you can be blamed if people don't like it or think that you're blaspheming. In order to take the praise, you have to take the blame. I remember once doing a gospel-type version of 'Danny Boy' and some people liked it and some die-hards said, "Oh, you can't do that with Danny Boy!" You can't have it all your own way and that's what's life is all about, I think.

I was watching your contribution to Mike Figgis' British blues boom documentary Red White and Blues and it showed a different and more contemplative side to Tom Jones as opposed to the Sex Beast of public perception. In that respect, how overdue do you think that Praise and Blame is?

Yeah, it is overdue. I think there have been different sides of me all throughout my recording career, and when you have an idea sometimes with a record company they want commercial; they've always talked me into doing commercial stuff, but it's hard to get across to a record company that you want to do a specialised thing, that you want to do something that is not pop – I'm not aiming for hit singles here. This is a concept album and I think that's a great thing.

Island Records, bless 'em, they asked for some Christmas music and I thought, Christ! If I can do than then maybe I can go deeper with it? They were almost on the right wavelength so I said, 'Look, if you want me to do something that is uplifting with a spiritual feeling then why don't we do it properly?'

I wanted to get more nitty-gritty. When people hear it, I want them to say, 'Wow! I haven't heard Tom sing quite like that before!'

**This has parallels with your mate Elvis' '68 Comeback Special doesn't it? His label wanted a Christmas show and they got leather-clad rock'n'roll instead...

TJ: Yeah, funnily enough, I watched that just the other night and I didn't realise that [Elvis manager Colonel Tom] Parker wanted a Christmas show and Elvis said to the director, "I really don't wanna do that."

So have you promised Island some Christmas songs in return then?

[Laughs] No! We did them two [demo] songs – 'Run On' and 'Did Trouble Me' - to show what we were trying to do and they're two really religious songs. Elvis did 'Run On' with gospel singers and put his own stamp on it so I wanted it even rougher, even more stripped down than he did.

You're Tom Jones with all that that implies. How much of a struggle is it for you to walk into a record label and say, "Look, this is what I really want to do"?

Well, it's kind of trial and error. You can't say, 'This is how I want to do it' in case they say, 'Well, we don't want to do it like that.' As I say, we tried those two songs with Ethan Johns who, God bless him, is well respected and Island have been wanting him to produce some of their other artists. But when he was asked to do me, he said, 'Great! That's something that I want to do.'

How did you and Ethan Johns hook up in the first place?

I was thinking about this spiritual-type music and who to do it with so Island suggested that we meet up and I met him at Apple Studios. I liked what he said: 'We'll go in the studio, kick around a couple of songs and see which way we can do the best with them. You sing 'em the way you feel 'em and we'll back you up.'

And when we did it, everyone was thrilled.

**There's been a move in the wake of Johnny Cash's American Recordings for artists of a certain vintage to interpret contemporary music in a roots style or the sound that made them famous. You've gone direct to the source material here instead. Why?

There were so many of these really good, spiritual gospel-type songs around but you've got to be careful that they don't get overdone as well, you know? I took quite a while getting to know these songs and I listened to the authentic versions like Sister Rosetta Tharpe's 'Strange Things' and I said, 'That's it! That's what I want!' I wanted to do them in a way that related to me and my early roots, when I was singing in the pubs and clubs of Wales with just three guitars and drums.

How much of the real Tom Jones is in these songs?

When you sing songs like these, it does touch you. If you're going to sing those lyrics, it's got to mean something. It's not like singing a song that I've got nothing to do with because these are very touching songs and they make people think. If my versions of these songs don't touch people then I've missed the mark.

I was watching early footage of you performing [1964 single] 'Chills and Fever' with you fronting a band. Do you have any regrets about not continuing in that format?

Well, yeah but I wanted to do other things as well. I still wanted to do stuff like 'It's Not Unusual' and 'Green Grass of Home' because when I had a band we did that stuff and it got me through the door, but I was also doing 'Great Balls of Fire' onstage. When someone came to see me [in the early days] they'd get 'It's Not Unusual' because it was more or less soul music. I was very much influenced by soul because it was very much like gospel music and the stuff done by Wilson Pickett, Sam Cooke and Solomon Burke. That's the kind of stuff I was doing even before I had a hit record.

You've worked with a whole variety of artists over the years from Janis Joplin through to Wilson Pickett and many others. You've been pretty blessed in that you've covered so many bases.

Well, that's why ABC wanted me to do the 'This Is Tom Jones' TV series back in the 60s. They thought that if I hosted the show I'd be able to do duets with more or less anybody because my repertoire was so big. I was always pushing for rock'n'roll people to be on the show but when I started it was more middle-of-the-road. I said to the producers, "If you want Barbara Eden from 'I Dream of Jeanie' on the show then I want Wilson Pickett and I've got to have Jerry Lee Lewis." And they said, "Jerry Lee Lewis? But he hasn't done any TV in years" and I said, "I don't care! Give me my bloody guests! And I want Janis Joplin! And I want Ray Charles! And I want Aretha Franklin!" And I got them all!

The Stones and The Animals and the other British invasion bands were always mystified that mainstream America had never heard these artists. Was that your experience too?

Absolutely! As far as the American bluesmen were concerned, I liked Big Bill Broonzy and when I was being interviewed in '65 when I first went over there they said, 'Where are you getting your influences from?' because they thought I sounded black; 'It's Not Unusual' was being played on black radio. To me, that was a pop record but they said, 'No, it's your timing and the tone of your voice – it's not white!'

When 'It's Not Unusual' came out over there, there was a fella called Lloyd Greenfield who'd booked me on the Ed Sullivan show and this black DJ called him and said, 'I hear that Tom Jones is coming over. You've got to bring him up to the radio station' and Lloyd said, 'But he's white' and the DJ said, 'No! Whoever is singing this song is not white.' And Lloyd said, 'But he is' so the DJ said, 'Can I give you a bit of advice? If you put his album out before the Ed Sullivan show, don't put his photo on the cover!' Because a lot of black artists didn't put their picture on the cover [so as not to alienate white audiences] and it was the reverse with me.

Did that upset you? Chris White from The Zombies was telling me about the package tours that they did in the US with a lot of their favourite black musicians. He loved doing them but he hated the racial segregation that he encountered at diners and places like that.

Funnily enough, I did a couple of tours with The Zombies; we all toured in '65 and I was on the Dick Clarke Caravan of Stars tour and they were on some other tour, and sometimes we would be in some city and the two tours would come together and we'd go on the same show.

But when you're on a tour with black entertainers and you have to stop at these roadside cafes, sometimes the whites would have to go in to get the food and sometimes they'd have to go in and get the food and bring it back to the coach. So I thought, Jesus Christ! It's unbelievable!

You know, in 1965 I'd have thought all of that shit would have been over! I knew segregation had been happening in the Second World War because being born in 1940 I saw a lot of black troops in Pontypridd just before D-Day and the black soldiers would walk on one side of the street and the white GIs would walk on the other side of the street. You know, I saw that when I was a child! I used to say to my father, 'They've all got the same uniforms on but they're walking on different sides of the street' and my father said, 'They don't mix; they're segregated' and I thought, Jesus Christ! That was when I was a child but I couldn't believe seeing it in '65. I thought that shit had gone out of the window by then.

You've hung out with the likes of Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr, Janis Joplin and Jerry Lee Lewis among many others. How is it that you've managed to avoid the usual trapping of fame such as drugs, madness and an early death?

Well, I was never interested in drugs because I've always liked a drink. And I like drinking; I really enjoy the taste of it. I love certain drinks and I love the taste of British beer; you know, real beer on tap.

A lot of British people drink Stella which is a lager. Jesus! That's not even real beer! People tell me that it's really good and I'm like, 'Yeah, right!' I don't want to put Stella down but some people drink to get drunk and I saw that with drug taking. People were taking drugs to get high and they weren't really enjoying the experience. You know, with cocaine – I saw people in bathrooms in restaurants snorting lines and I thought, Jesus Christ! It looked like Fagin counting his money!

I've been at parties where people have been snorting off tables but it was never attractive to me. I've never tried it once. I've never even smoked a joint. But I have been in a room and gotten high off of it because everyone else was bloody smoking it!

I've tried to analyse this and I think maybe you go into unknown territory – you see people do it but there's no label on the bottle. When I drink, I want to know what I'm drinking and I want to know what the percentage of alcohol is in that bottle. I don't want someone pouring me a drink of something that I don't know. And I think that with drugs it's like that. I wouldn't want to take a chance on something where I don't know what the effect will be. I know the effect of beer and I know what it is with wine and I know what it is with spirits but I wouldn't want to dabble with drugs. That saved me from going down that road.

But drink has contributed to the demise of quite a number of artists over the years, hasn't it?

Oh sure! You know, I do enjoy a drink but I've got to keep my eye on the clock. If I've got to do something the following day then I've got to get my eight hours sleep. In Wales we call everyone by their nicknames, usually by their professions, like I'm 'Jones the Voice' and Kelly Jones from The Stereophonics has got a new one for me. He calls me 'Tommy Eight Hours'!

That makes you sound like someone from Goodfellas!

Yeah! See, whenever I've been out with them there always comes a point when I say, 'Well, it's getting late now, lads!' Maybe they can take it but I need my eight hours.

I've always tried to keep a handle on it because if you do drink too much there's always the dehydration the next day and you're up against it. If you've got an early thing to do, like TV or something, you can't go on looking like shit and more likely sounding like shit! So I've seen a couple of those cases and I've though, No, that don't work!

I tried all of that at the beginning when you start to make money and the fame that comes fast with your first hit record and you've got to watch yourself then.

Given your love of ale, it must be difficult to get a decent pint in LA?

Well, nowadays they import quite a lot of British beer and you can even get Welsh beer. They haven't got Brains yet but I'm drinking Felinfoel Double Dragon and it's great. I get it from the supermarket and it's very nice. It's the closest you can to Wales without actually going there!

Have you tried any of the American microbrew stuff like Sierra Nevada Pale Ale and Sam Adams?

Sam Adams is good as long as it's the ale. Nine times out of ten it'll be lager but they do a nice ale as well.

What's the biggest misconception about Tom Jones?

The thing that hits me the most is the sexual part on stage. You know, the knicker throwing and all that. That overtook the talent which I never meant for it to do. I always thought that my voice could push through anything, you what I mean? People always thought, 'Oh, it's Tom Jones: throw knickers at him!' And I always thought I could overcome that with my voice but sometimes you can't. If you start messing around too much on stage with stuff that's been thrown at you then you'll get caught. See, we're back to Praise and Blame again! I created it myself and it's bit me on the arse, really. These days, if people throw things on stage then I don't bother with them. You know, I don't pick them up and I don't do shtick with them.

See, coming from a working class background, if someone throws something at you in the pub then you make something out of it and you use it to your advantage, so when they started throwing underwear at me I was having a ball with them, you know?

You know, when The Beatles went on stage, the kids didn't give a shit what they were playing – they were just screaming. And at one point, I don't think people cared about what I was singing as long as I had tight pants and they could throw knickers at me.

Are you going to take Praise and Blame on the road in that stripped down band format?

We're going to try to some shows in smaller venues and we're trying to put them together now so we can do a few showcases. But I couldn't do a whole show like that because the album's not long enough and I'm onstage for at least 90 minutes.

See, when people come to see an entertainer... it's fine if you do a specialised show like a showcase or a club and you explain what you're doing but if people are coming to see a show and [you] only do that album and don't do anything they know, I think that you're short-changing the people then. But I'll definitely be doing a lot of the songs in the show. And we're going to try to do a TV show with the album line-up.

You're just a few weeks away from your 70th birthday. Got any special planned?

I'm going to be spending it here in LA because my wife, she doesn't travel anymore. Not since 9/11 – it shocked the shit out of her. After we flew back to America we haven't flown since and that's a bit of a bother. Anyway, she's a quiet person and she doesn't like parties – well, she did when she was younger, of course – and I'd like to be with her for my 70th birthday. That's not to say that I won't be seeing my friends in England for a few bevies but it just won't be my actual birthday.

Given such dedication, would you call yourself a romantic?

Yeah, I still love my wife and we still have dinner together, just me and her. And I'm fine with it. I enjoy it and she loves it.

What have you got left to achieve? Surely there shouldn't be any reason for you to get out of bed in the morning?

No, but that would be very boring though. I can only take short periods of time off, you see. I sing around the house and my wife, she says to me, 'I think it's time you bloody went out on the road.' You know, I get my guitar out and I'm singing songs to her – which she likes – but she says, 'I know where this is leading and you've got to get back on stage again.'

It's funny because I'm working as much as I ever did and when I was younger I thought I'd have slowed down by now. My wife asked my original manager Gordon Mills, 'Does Tom have to tour as much as he does?' and he said, 'Oh, don't worry Linda. When he gets older he'll slow down – it's a natural thing.' So my wife now says, 'When's this slowing down, then?' To be honest with you, I don't think it will. I've just done shows down in South America, Australia, New Zealand, the Far East, the Middle East and South Africa. I've finished a three-month tour just now.

But I still want to make more albums of different kinds of music; you know, I don't like to get stuck in a rut. Some people love a certain kind if music and they play it and that's all they play, and God bless 'em, but I like to change things round a bit. I love singing 'Kiss' as much as I love singing 'Boy From Nowhere'. See, to me, it all works. I can get parts of me out there that you can't do with one song. You need a mixture of stuff to get different parts of me out there. I take people on a musical journey while getting kicks myself and I'm loving it! When you get that reaction from the audience, it's like a bloody drug. That's the drug I've indulged in the most: applause. I can't sit around the house as there's no adulation to be had!

Since Jones was not a songwriter, the direction of his music was limited to the songs that were available, he explains. The same kind of material kept coming his way. "They were iconic records. I'm not saying I don't like them," he adds of the hits. "When Burt convinced me to do that song, it took a while. He did say, 'This is not a rhythm & blues song.' Soul music had kicked in by then, and I wanted to do Wilson Pickett songs, Solomon Burke, Sam and Dave, and Otis Redding. But I wasn't getting the songs."

Since Jones was not a songwriter, the direction of his music was limited to the songs that were available, he explains. The same kind of material kept coming his way. "They were iconic records. I'm not saying I don't like them," he adds of the hits. "When Burt convinced me to do that song, it took a while. He did say, 'This is not a rhythm & blues song.' Soul music had kicked in by then, and I wanted to do Wilson Pickett songs, Solomon Burke, Sam and Dave, and Otis Redding. But I wasn't getting the songs."

Mike Ragogna, The Huffington Post - Posted: July 27, 2010 01:11 AM

Mike Ragogna: Your new album Praise & Blame has a very stripped-down sound. What was your philosophy going into making this record?

Mike Ragogna, The Huffington Post - Posted: July 27, 2010 01:11 AM

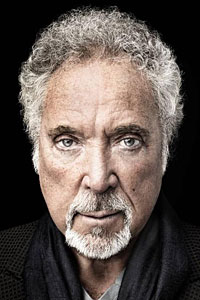

Mike Ragogna: Your new album Praise & Blame has a very stripped-down sound. What was your philosophy going into making this record? Q had the pleasure of meeting up with Wales' greatest export Sir Tom Jones last week to discuss his rootsy new album Praise And Blame. Autographing an album for a fan, he pauses to spell 'Happy Birthday'. "I'm dyslexic, you know?... I know 'birthday' is 'ir' but it should be 'er' - I mean, that's how it sounds, 'berthday'." Maybe it's learning difficulties. Or perhaps it's just a matter of Wales having never left Tom Jones; which would be one explanation for why he's recorded an album of the music he enjoyed in church as a boy in Pontypridd. Mostly, the Tom Jones we see now is laying everything bare.

With that in mind, when a rep from his record label Island brandished the whole thing "a joke", you'd think it would hurt. But as the Godfather of pop would probably have it, it's just par for the course in the pop industry. Speaking authoritatively (and emphasising every phrase in that gravelly Welshman's tone) about the gospel origins of rock'n'roll and getting back to where it all started, Tom explains how he's been told he doesn't "fit in" since the release of his first hit single, It's Not Unusual. It would appear however that, for this "joke", it's Tom Jones who may just have the last laugh. Seventy years old; his voice better than ever; still "kicking the shit out of everything": 'unusual' doesn't do him justice.

Q had the pleasure of meeting up with Wales' greatest export Sir Tom Jones last week to discuss his rootsy new album Praise And Blame. Autographing an album for a fan, he pauses to spell 'Happy Birthday'. "I'm dyslexic, you know?... I know 'birthday' is 'ir' but it should be 'er' - I mean, that's how it sounds, 'berthday'." Maybe it's learning difficulties. Or perhaps it's just a matter of Wales having never left Tom Jones; which would be one explanation for why he's recorded an album of the music he enjoyed in church as a boy in Pontypridd. Mostly, the Tom Jones we see now is laying everything bare.

With that in mind, when a rep from his record label Island brandished the whole thing "a joke", you'd think it would hurt. But as the Godfather of pop would probably have it, it's just par for the course in the pop industry. Speaking authoritatively (and emphasising every phrase in that gravelly Welshman's tone) about the gospel origins of rock'n'roll and getting back to where it all started, Tom explains how he's been told he doesn't "fit in" since the release of his first hit single, It's Not Unusual. It would appear however that, for this "joke", it's Tom Jones who may just have the last laugh. Seventy years old; his voice better than ever; still "kicking the shit out of everything": 'unusual' doesn't do him justice. ‘Who in the hell is Tom Jones?’ spat Charles Bukowski. It’s a good question. The Tom Jones he wrote about in Hollywood is a slick Vegas showman, “his shirt is open and the black hairs on his chest show. The hairs are sweating.” The Tom Jones I meet is a white-haired Welshman about to release an album of blues and gospel so out of character that the vice-president of his own record label called it a “sick joke”. So just who in the hell does Tom Jones think he is?

‘Who in the hell is Tom Jones?’ spat Charles Bukowski. It’s a good question. The Tom Jones he wrote about in Hollywood is a slick Vegas showman, “his shirt is open and the black hairs on his chest show. The hairs are sweating.” The Tom Jones I meet is a white-haired Welshman about to release an album of blues and gospel so out of character that the vice-president of his own record label called it a “sick joke”. So just who in the hell does Tom Jones think he is?